In a recent fourth-grade class meeting, a size 15 pair of loafers, once owned by former NFL player Barrett Jones, rests on the floor. An energetic group of boys admires the shoes — all waiting for a chance to wear them. The idea of “walking a mile in someone else’s shoes” is on full display. One of the students slips into the enormous shoes and begins his journey walking around the room while PDS school counselor Tom Edwards reads out an all-too-common scenario.

You find out that you aren’t invited to a party that many of your friends are attending. How does that make you feel? As the student walks, he describes how someone might feel in that situation. Sad. Embarrassed. Mad. Betrayed. Surprised. Worried. Left out. The depth of discussion is not surprising. What might be surprising is that the scenarios used in the exercise are written by the students themselves. They actively engage in every opportunity to role-play some of their own experiences. Yes, they are young, but PDS boys are quickly learning the value of becoming emotionally intelligent.

IQ vs EQ

Often, in a boy’s mindset, the definition of being successful in school means being the first to finish his work, the fastest reader, or the one who has the most to say (whether or not the comments are on topic!). In their minds, fast equals smart and the only path to success. PDS teachers are always working to combat these misguided interpretations of intelligence. While the intelligence quotient (IQ) may be an indicator of success in academics and measure how well a student is able to process, reason, and store information, IQ is only partly responsible for how successful a student will be in life.

Almost 30 years ago, psychologist Daniel Goleman ignited a conversation about emotional intelligence (EQ) when he published Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. According to Goleman, EQ is the measure of one’s ability to recognize his or her own emotions and the emotions of others. Goleman states that emotional intelligence accounts for 80% of career success. He goes on to say, “Most people are hired for their intellect and business expertise — and fired for a lack of emotional intelligence.”

Studies continue to support Goleman’s work and the idea that emotional intelligence is a learned skill set, one that can and should be taught in schools. Yet, the vast majority of schools fixate on academic abilities and ignore social and emotional learning. The PDS mission is a constant reminder of the very important task we face daily — glorifying God by developing our boys in wisdom, stature, and favor with God and man. The wisdom we are called to impart, a combination of academic, spiritual, social, and emotional learning, is the foundation for a successful future, a future that finds favor with God and man.

Along with our fantastic faculty, PDS is fortunate to have Tom Edwards, a licensed clinical social worker, on staff as the school counselor. Mr. Edwards spends a great deal of time meeting with first through sixth graders teaching them about the importance of remembering their ARMOR, an acronym he developed in his private practice to represent the most critical components of emotional intelligence.

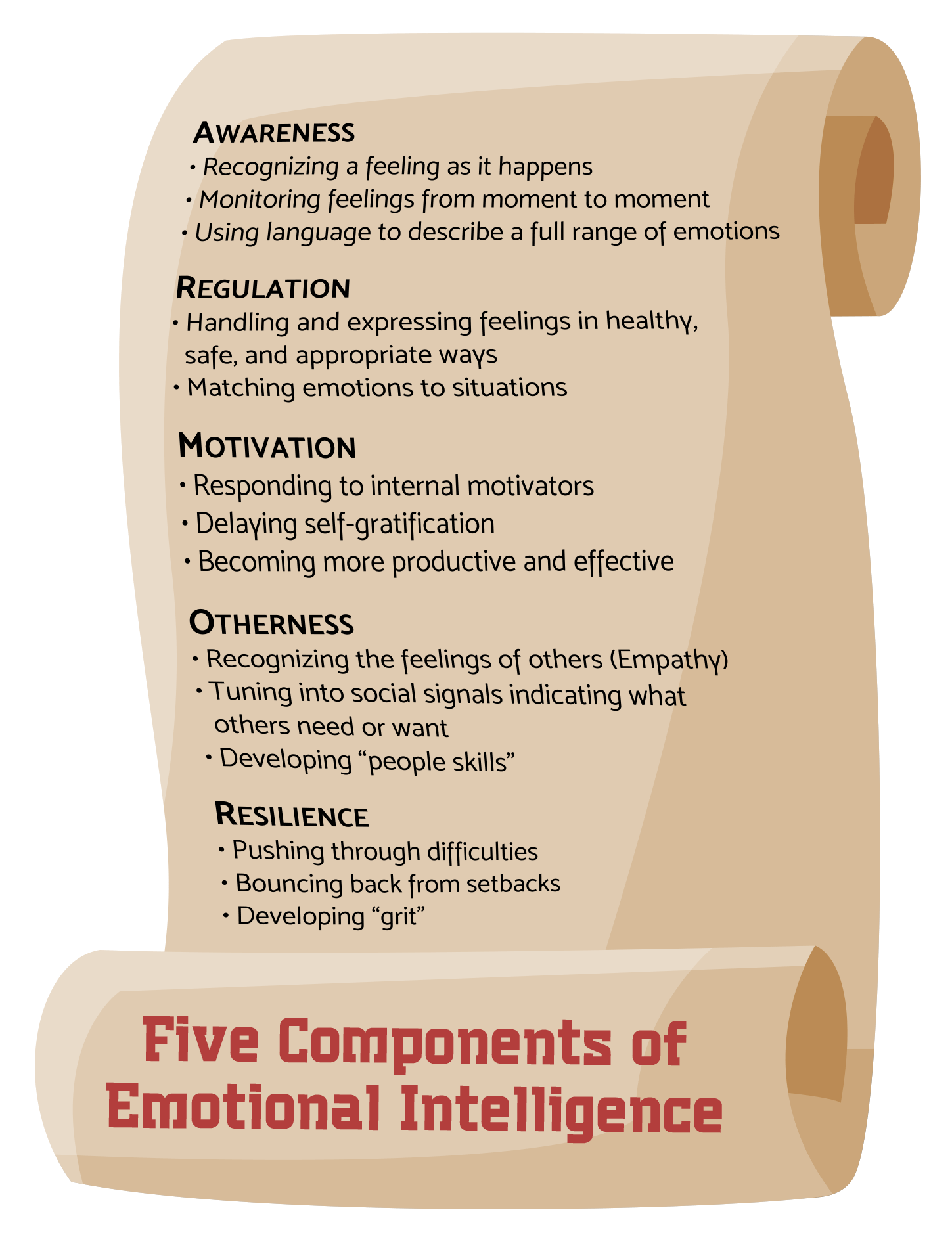

5 Components of Emotional Intelligence

Awareness

One component of being emotionally intelligent is the ability to recognize a feeling as it happens and monitor those feelings from one moment to the next.

A common stereotype of boys is that they are not in touch with their feelings. In actuality, boys experience a full range of emotions, but they are slower to develop the language skills necessary to express what they are feeling. They don’t always know the verbage associated with the varying degrees of happy, mad, sad, and scared, the most common words used to express emotion. Also, it can be difficult for young students to decode nonverbal cues from others’ facial expressions.

One component of being emotionally intelligent is the ability to recognize a feeling as it happens and monitor those feelings from one moment to the next.

A common stereotype of boys is that they are not in touch with their feelings. In actuality, boys experience a full range of emotions, but they are slower to develop the language skills necessary to express what they are feeling. They don’t always know the verbage associated with the varying degrees of happy, mad, sad, and scared, the most common words used to express emotion. Also, it can be difficult for young students to decode nonverbal cues from others’ facial expressions.

Through both class meetings and seminar classes, PDS students are exposed to an expansive “feeling” vocabulary and practice using words from it on a regular basis. Younger students use a feelings chart with facial depictions as they talk through a variety of emotions.

Regulation

Everyone has experienced a hot-button moment. Something that wouldn’t normally be a big deal sets off a range of emotion. In those moments, the amygdala, the area of the brain that helps regulate emotions, is hijacked, and the fight-or-flight response is activated. Generally, the brain’s frontal lobes are a bit more rational than the amygdala and help decipher whether the threat is of great concern. Most often the emotional outburst de-escalates.

Everyone has experienced a hot-button moment. Something that wouldn’t normally be a big deal sets off a range of emotion. In those moments, the amygdala, the area of the brain that helps regulate emotions, is hijacked, and the fight-or-flight response is activated. Generally, the brain’s frontal lobes are a bit more rational than the amygdala and help decipher whether the threat is of great concern. Most often the emotional outburst de-escalates.

This relationship between the amygdala and frontal lobes works well to regulate emotions for grown adults. But for young males, frontal lobe development is slower; in fact, it continues developing well into a male’s early 20s. This biological truth is important for our boys to understand. As PDS students become more self-aware, they learn to match their emotions appropriately to situations and figure out the best ways to handle and express feelings in healthy, safe, and appropriate ways.

Motivation

There’s no doubt that every PDS student loves to receive a Happygram, a handshake, or a high-five. These extrinsic motivators are built into the life of our school to make sure that our boys feel known, nurtured, and loved. But these alone are not enough of a driving force to modify their behavior. Students who are able to recognize and respond to internal motivators are much more successful in academic and social settings. As children grow, it’s tempting to praise every new achievement and tell them how smart they are, but this is counterproductive.

There’s no doubt that every PDS student loves to receive a Happygram, a handshake, or a high-five. These extrinsic motivators are built into the life of our school to make sure that our boys feel known, nurtured, and loved. But these alone are not enough of a driving force to modify their behavior. Students who are able to recognize and respond to internal motivators are much more successful in academic and social settings. As children grow, it’s tempting to praise every new achievement and tell them how smart they are, but this is counterproductive.

A classic study of U.S. fifth graders by Carol Dweck and Claudia Mueller emphasized the importance of praising effort over intelligence, and the results showed that the students who were praised for intelligence were less likely to focus on being successful, avoided more challenging tasks, and generally found less pleasure in the work being asked of them. As PDS teachers look to share praise with students, the focus is placed on praising their effort or particular strategies used to accomplish a goal. As students mature and learn to respond to their own internal motivators, they grow in their ability to delay self-gratification, become more productive and effective overall, and reap much larger long-term rewards.

Otherness

Michele Borba, author of Unselfie: Why Empathetic Kids Succeed in Our All-About-Me World, says students today are growing up in a “self-absorbed craze.” The pressures of self-promotion, personal branding, and self-interest negatively impact a student’s ability to recognize the feelings, needs, and concerns of others. According to Borba, there has been a 40% decrease in the empathy levels of teens over the past 30 years. Along with a sharp decrease in empathy, it is not surprising that narcissism is on the rise.

Michele Borba, author of Unselfie: Why Empathetic Kids Succeed in Our All-About-Me World, says students today are growing up in a “self-absorbed craze.” The pressures of self-promotion, personal branding, and self-interest negatively impact a student’s ability to recognize the feelings, needs, and concerns of others. According to Borba, there has been a 40% decrease in the empathy levels of teens over the past 30 years. Along with a sharp decrease in empathy, it is not surprising that narcissism is on the rise.

What is PDS’ response to this? Teaching empathy! Our boys are asked daily to take on the perspective of others and think about how to love one another well. Through our Seven Virtues of Manhood, the students are given explicit definitions for what it means to be a True Friend and a Servant Leader, two virtues that are especially focused on helping students tune into social signals and develop a heart for others. In the EDGE, our boys are asked to evaluate human-centered problems, develop empathy with the issue, and generate solutions that could have a real-world impact.

Recently Mark Fruitt, Principal of the Elementary Division, challenged PDS students with an essential question, “Are you tough enough to be kind?” This question serves as a reminder that kindness must be practiced on a daily basis even though it can feel like a more difficult road to take in certain situations. At PDS, we see what research confirms: Empathy can and should be taught, and our boys are growing as a result of it.

Resilience

When PDS boys hear that inventor Sir James Dyson designed over 5,126 failed vacuum prototypes before finding success, they can hardly believe their ears. Resiliency is not just the ability to recover from a setback but to thrive while doing it, pushing through difficulties, digging deep, and developing grit. In lower elementary grades, this might mean reading a book multiple times to build fluency and understanding, practicing math facts over and over until mastery is reached, or navigating the social dynamics of recess. In the upper elementary grades, students might be balancing the demands of multiple classes or trying to maneuver competitive sports. PDS teachers are quick to model resiliency, talk openly about making mistakes, and intentionally let students enter and wade through frustration zones before stepping in to assist. When it comes to developing resilient students, providing opportunities for failure is the key to success.

When PDS boys hear that inventor Sir James Dyson designed over 5,126 failed vacuum prototypes before finding success, they can hardly believe their ears. Resiliency is not just the ability to recover from a setback but to thrive while doing it, pushing through difficulties, digging deep, and developing grit. In lower elementary grades, this might mean reading a book multiple times to build fluency and understanding, practicing math facts over and over until mastery is reached, or navigating the social dynamics of recess. In the upper elementary grades, students might be balancing the demands of multiple classes or trying to maneuver competitive sports. PDS teachers are quick to model resiliency, talk openly about making mistakes, and intentionally let students enter and wade through frustration zones before stepping in to assist. When it comes to developing resilient students, providing opportunities for failure is the key to success.

When Mr. Edwards is not meeting with an entire grade-level of students, his office is often filled with small groups of students or even those who wish to visit one-on-one. PDS students know that his office is a safe place to talk — or even play a game of UNO as a break from school work. Whatever the reason for the visit, PDS boys leave with a deeper understanding of what it means to be emotionally intelligent. Their EQ is galvanizing strength — one piece of ARMOR at a time.